ABODE AND POINT TO THE EYE

Saygun Dura’s current exhibition at Millî Reasürans Art Gallery is a meditation on migration envisioned through the prism and mechanisms of evolution, including natural selection and nature’s imperative to preserve and reproduce itself. As a photographer in the field of advertising, an educator, and an artist, Dura’s career spans nearly three decades. He has been a lecturer at several universities, including Mimar Sinan University and Bahçeşehir University. He has also exhibited extensively in Turkey and internationally. His works feature in private and museum collections.

The wealth of Dura’s technical experience is evident in this body of complex, large-scale colour photographs taken underwater, at varying depths. Yet, while Dura’s work is technically impeccable, it also transcends the limits of professional expertise. He continuously adapts his methods to capture and convey the conceptual virtues of the subject, thus moving beyond merely their representational quality. While the closeness to his subject reflected in the images implies a performative engagement and participation, Dura is not an action photographer per se. Instead, he photographs life in a staged manner, meticulously preparing and anticipating the results. It is as if he set up the scene on a studio platform with a level of detachment from the subject, resembling Jeff Wall’s impartial approach in ‘An Octopus’ (1990). A close study of Dura’s compositions, lighting, and colour, shows that he is in total control. The actual element of surprise is not in the encounter with the unexpected but in the artist’s ability to control the apparatus of photographic image-making.

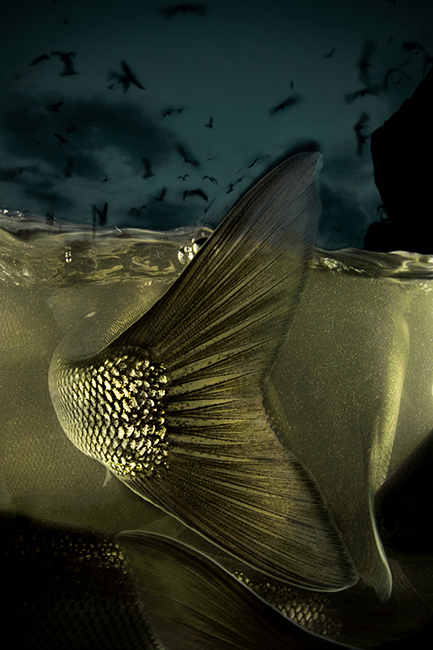

Saygun Dura’s photographs appear to be taken on the threshold between land and sea, air, and water. His subjects gasp for air, literally and metaphorically. There are two distinct series of large-scale photographs in the show, looking at the frenzy of activities on the surface and the eery, otherworldly calmness at the bottom of the lake. One of the series represents the migration of the pearl mullet, known to be the only species to inhabit Lake Van in Eastern Turkey. Whereas there is a plethora of subtexts in the depiction of this almost ritualistic act of survival, the images are primarily concerned with matters of urgency, presenting the universal codes of nature to reproduce, adapt and evolve. Lake Van and its surroundings are on the geographical trajectory of migration paths from East to West and have recently witnessed an influx of asylum seekers coming from Central Asia. Migrants use the waterways of this vast lake to transition rapidly into the interior of the country. Moreover, the geographical position of the lake is on the migratory trajectory of many other species from the pearl mullet to birds such as the pelican and the flamingo and provides much-needed resources. The photographs thus present a drama of life and death, where the seagulls (Larus armenicus) are in pursuit of the shoaling and schooling fish for their

survival. The onlooking audiences peering into the dark waters from above are blurred yet visibly witnessing this drama of continued existence. The act of impartial participation devoid of empathy is seen through the gaze of the photographer, who in turn is also being observed as the subject is located between him and the gaze of the expectant onlookers on shore. The proximity of Dura’s picture plane to the action creates a further layer of drama and allows the audience to participate in this fluid transition of life and fate. Sigmund Freud defines a drive as “an urge inherent in organic life to restore an earlier state of things”, and as the inorganic precedes the organic, “the aim of all life,” he concludes in his famous phrase, “is death” (Foster, 1993, p.10).

Dura’s experiential engagement with his subject is also phenomenological. Migration is constituted of three phases, leaving the home, a liminal or transitional phase and finally, arrival. The physicality and the laborious and dangerous act of moving bodies through space and water are very much evident in Dura’s images where the fish have become easy prey for the birds. He has chosen to capture the process at the point of departure or leaving home, rather than in transit upstream in the adjoining rivers. The scenes captured in the photographs seem at once familiar yet uncanny. According to Freud, “An uncanny experience occurs either when repressed infantile complexes have been revived by some impression, or when the primitive beliefs we have surmounted seem once more to be confirmed.” (Foster,1993, p.8). What is also striking is Freud’s examination of the evil eye, identified as “animistic mental activity”, a thought entertained correspondingly by the surrealist cohort. Featured close-up in many of the photographs, the eye of the fish is not evil, it is full of fear. It is a gaze towards nowhere.

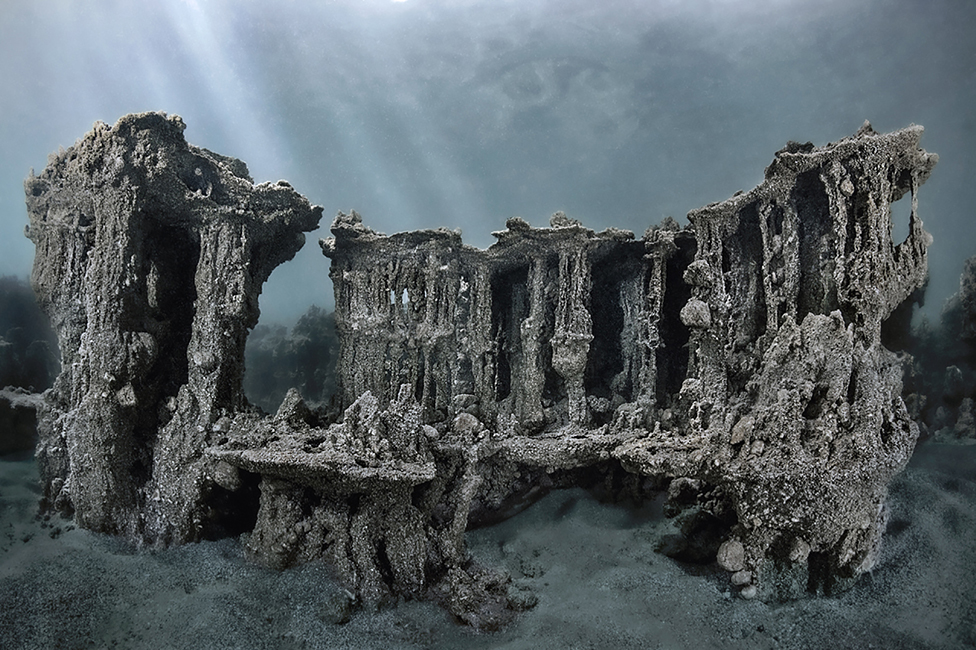

The second body of works depicts microbialites, the pearl mullet’s natural habitat in the lake’s shallow ends. Yet in this case, they are depicted as empty or abandoned by their tenants. Possessing the largest organosedimentary deposits (microbialites) reaching several meters in height, Lake Van is quite unique (Kempe et al., 1991). The scenes are eerie and ghostly. The images simultaneously capture the contrasting feelings of serenity, silence, and drama existing at the bottom of the lake. Are we looking at the remnants of a lost world, like Atlantis, or otherworldly landscapes? Are these structures and objects alive or inanimate? In the context of this exhibition, the calm and the stillness of these fantastical underwater seascapes offer a contrast with and are suppressed by the drama above. There are also remnants of abodes and vessels like the two images in the show depicting an old sunken ship that maintained its function as a haven, this time harbouring other species. They remind us that the perils at sea are unforgiving and that we are conceivably looking at hell rather than paradise. The ship represents the migration vessel par excellence but also a kind of Foucauldian heterotopia, free of the everyday realities (Foucault, 1967). Van is an area where there are multiple tectonic shifts, geological as well as historical and socio-political. The microbialites are nature’s dramatic creations “produced by benthic microbial communities interacting with detrital or chemical sediments” (Kempe et al., 1991) and represent a surreal world of imaginably exotic gardens like Max Ernst’s ‘Conscious Landscape’ (1942). They may also be analogous to his paintings ‘Swampangel’ (1940) and ‘The Eye of Silence’ (1943–44). The microbialites could be seen “in a state of relative (de)fusion”, visitors from primordial times that refer to the primal “world of uncanny signs” (Foster, 1993, p.200).

Examining the compositional elements of Dura’s photographs reminds us of Jeff Wall’s concerns that there is no outside or life to his images “since they are constructed” (Wall, 1996, p.9), whereas in conventional photography there is all that is outside of the picture plane which has been left out. In Dura’s evocative images, the threshold of the surroundings has been omitted and similarly, there is no ‘greater whole’ outside the image. In Wall’s terms, they appear to be almost ‘cinematographic’. Indeed, Dura’s photographs are concerned with the liminal spaces created by water, air, and land.

Saygun Dura’s exhibition is not merely a vehicle for reflecting the technical abilities of the photographic image and its legacy but represents the potential to uncover universal truths and codes. Although all images are in colour, the palette used is primarily monochrome. Omitting or reducing the use of colour, allows the subject matter to be embedded in the chiaroscuro of contrasting light, shadows, and reflections on the surface of the lake. As a professional photographer and a skilled diver, Dura has a unique place in the art world. His thinking and his philosophy are reflected in the presented series of photographs. The broad range of his studio constructed images and underwater photographs continuously enriches his vocabulary and the expansive pictorial languages he employs, borrowing largely from the surrealist thinking and imagining tradition. This exhibition represents a pivotal point in his approach as a photographer.

Prof. Dr. Ergin Çavuşoğlu

Saygun Dura

Saygun Dura

Saygun Dura

Saygun Dura

Saygun Dura

Saygun Dura

Saygun Dura

Saygun Dura

Saygun Dura

Saygun Dura

Saygun Dura

Saygun Dura

Saygun Dura

Saygun Dura